A new installation at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City reprises the first one-man photography exhibition MoMA ever mounted: “American Photographs” by Walker Evans, which opened seventy-five years ago, in 1938. More than fifty of the original one hundred prints by Evans are included in the new show, which runs through January, 2014.

In 1938, the thirty-five year old Evans was not as famous as he is now, even though most of his best work was already behind him. Several prints in the show, for example, come from Evans’ 1935-36 trip through the rural South, when he took some of the best-known photographs in U.S. art history.

In 1938, the thirty-five year old Evans was not as famous as he is now, even though most of his best work was already behind him. Several prints in the show, for example, come from Evans’ 1935-36 trip through the rural South, when he took some of the best-known photographs in U.S. art history.

The picture below is of Allie Mae Burroughs, wife of a cotton sharecropper in Hale County, Alabama.

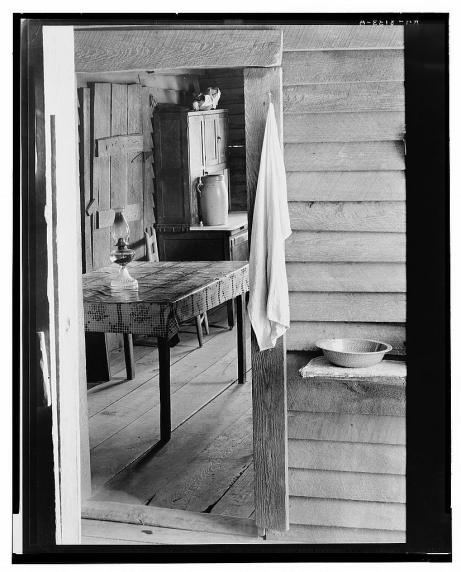

Here is Evans’ photograph of the interior of Allie Mae’s cabin.

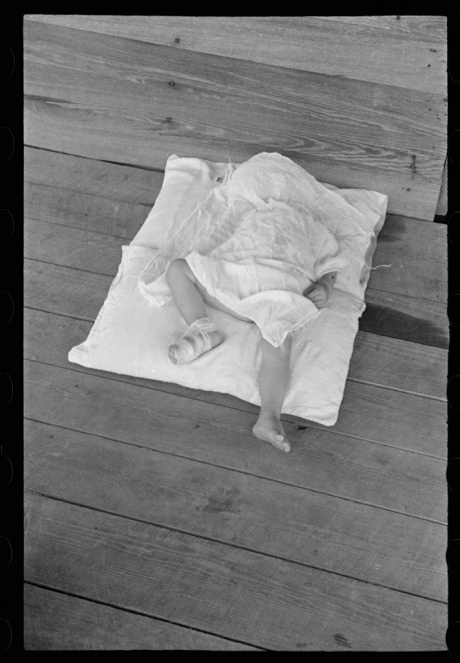

And here is a shot of Burroughs’ son, Othel Lee (“Squeakie”), asleep on the floor:

You can perhaps see why Lincoln Kirstein once praised Evans’ photographs for “their exhaustiveness of detail, their poetry of contrast, and, for those who wish to see it, their moral imagination.”

The pictures above would later appear in James Agee and Walker Evans’ 1941 classic Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. But Evans took many other photographs during the 1930s and in places besides Hale County, Alabama: he also traveled to and documented life in Mississippi, South Carolina, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and other locations. The slideshow below displays several of Evans’ photographs from the mid-1930s:

After reading about the MoMA exhibit, I got to thinking about Evans’ work, not only because I thought it might help me with my own multi-media work on place, but because I was curious about who controls his photographs today, blogging having made me sensitive to issues of copyright and intellectual property. As it turns out, according to Wikipedia, “The Metropolitan Museum of Art is the sole copyright holder for all works of art in all media by Walker Evans.” But there’s an important exception: a group of approximately 1,000 black and white negatives (including all those reproduced in this blog post) held by the U.S. Library of Congress, works that are thus in the public domain and free of all copyright restrictions.

The pictures are available because Evans was paid to take them by the U.S. government – more specifically, by the Resettlement Administration (1935-1936) and its successor, the Farm Security Administration (1936-1942), both New Deal agencies created by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to combat rural poverty in depression-era United States. As part of that effort, the head of the Information Division of the RA/FSA (and the later Office of War Information), Roy E. Stryker, sponsored a pictorial survey of the country.

It was, according to a later account, “the most extensive photo-documentary effort ever carried out in the United States.” Stryker hired not only Evans but other talented photographers, including Arthur Rothstein, Ben Shahn, Gordon Parks, and Dorothea Lange (who took the famous “Migrant Mother” picture shown here). According to the Library of Congress website, “The project initially documented cash loans made to individual farmers by the Resettlement Administration and the construction of planned suburban communities. The second stage focused on the lives of sharecroppers in the South and migratory agricultural workers in the midwestern and western states. As the scope of the project expanded, the photographers turned to recording both rural and urban conditions throughout the United States as well as mobilization efforts for World War II.” The Library of Congress has more than 175,000 black and white film negatives from the project.

In that massive collection, it turns out, are 50 pictures taken by Walker Evans of a single block in New York City on a Tuesday morning in August, 1938. Although, at the time, MoMA was mounting a solo exhibition of his work, Evans was in search of employment. There are letters from the spring and early summer of that year in which he asks Stryker for work. It is not clear whether Stryker agreed to the project, if he paid Evans for the effort, or what he thought of the resulting photographs; but on August 23, 1938, Evans walked up and down East 61st Street in New York City, mostly between First and Second Avenues, taking 35mm black and white photographs of the morning’s scenes:

East 61st Street is, of course, still with us today, and I can see from Google Maps what it looks like, seventy-five years after Evans visited.

Here’s 311 East 61st Street in the summer of 1938, from the point of view of Walker Evans’ camera:

And here’s that same building today as depicted in Google Maps’ “street view”:

Here’s 345 East 61st Street in 1938:

And here it is today:

Here’s 1113 First Avenue in August, 1938:

Here’s that same streetscape today:

Perhaps even more striking than the street scenes are the portraits Evans took of the neighborhood’s residents, including children out of school for the summer.

Here’s another group playing nearby:

And here are some local adults, keeping watch:

It’s an extraordinary visual record of one morning in the life of a city block. And it’s available, without cost or restriction, to anyone with an Internet connection.

I’m proud of my government’s sponsorship of this creative work, undertaken during the worst economic crisis in our nation’s history. I’m impressed by the continued public stewardship of these artifacts by the Library of Congress. And I’m inspired by Walker Evans’ style of documentary photography – his patient but frank recording of this one, seemingly insignificant, corner of the world.

And I can’t help but ask: what if you took 50 photographs one morning of your immediate environment – the streets, buildings, people, and objects around you – as purely, yet compassionately, as you could. And what if you then made that work available to the rest of the world, for free and without restriction?

All historical photographs here are reproduced digitally from black and white negatives housed in the U.S. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection. Individual reproduction numbers are provided with each photograph. For information about rights and reproductions of FSA negatives, click here.

For more on Walker Evans’ August, 1938, photographs of East 61st Street in New York City, click here.

For another blogger’s attempt to re-create Evans’ morning on that block, click here.

For the Wikipedia article on Walker Evans, click here.

For the New York Times article on the 75th anniversary of Evans’ “American Photographs” exhibit at MoMA, click here.

For David Bollier’s 2002 Boston Review article on “Reclaiming the Commons,” including efforts to keep cultural knowledge and artifacts free and accessible to the public, click here.

For a contemporary photojournalism project modeled on the FSA, click here.

Other resources consulted for this blog post include Walker Evans, American Photographs (with an essay by Lincoln Kirstein) (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1938, 1962, 1988); Walker Evans, Photographs for the Farm Security Administration, 1935-1938 (New York: Da Capo Press, 1973); and Documenting America, 1935-1943, edited by Carl Fleischhauer and Beverly A. Brannan, with essays by Lawrence W. Levine and Alan Trachtenberg (Berkeley: UC Press, 1988).

This is a terrific post, David! I think that you have taken something that could have been a very interesting text based essay and you have created an infinitely more interesting alternative – a text that mixes printed text with various forms of clickable media (pictures, Google street view maps, and other outside Web sources) which results in something that is infinitely more interesting and engaging for an interested reader. I think that this post will be an excellent example of digital composition is capable of for students or any one else who is interested.